Digital poverty in quantity surveying practice

Abstract

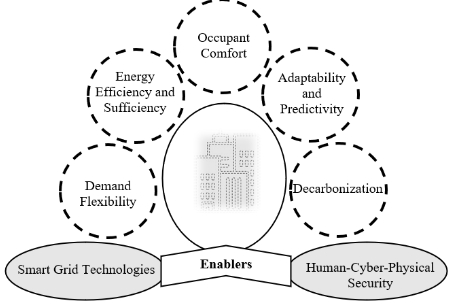

Background: Digitalization has profoundly impacted the construction sector, offering tools and technologies that promise increased efficiency, accuracy, and collaboration. Nevertheless, the integration of these digital solutions, notably Building Information Modeling (BIM), can be impeded by a set of fundamental barriers known as enablers of digital poverty. These enablers encompass a range of challenges that quantity surveyors face in Lagos State when attempting to embrace BIM and other digital tools. Objective: The objective of this study is to pinpoint, classify, and assess the factors that enable digital poverty when it comes to implementing BIM within the community of quantity surveyors in Lagos State, Nigeria. By understanding these enablers, stakeholders can develop targeted strategies to alleviate digital poverty and promote digital inclusion in the field of quantity surveying. Methods: A quantitative research method was utilized, employing a questionnaire survey to collect information from quantity surveyors in Lagos State. The questionnaire used in the study was designed to collect demographic data and evaluate the factors contributing to digital poverty. The collected data were analyzed using the mean item score and subjected to exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to uncover hidden groups or patterns among these contributing factors. Results: The EFA exposed five distinct clusters of enablers of digital poverty: Exploration Enablers—Factors related to creating an enabling environment for digital adoption, including limited financial resources, inadequate institutional arrangements, and lack of awareness; Incognizant Enablers—Factors reflecting a lack of knowledge and awareness, such as erratic power supply and insufficient government support; Compliance Enablers—Factors associated with the challenges of complying with new digital practices, including resistance to change from traditional methods and the scarcity of BIM specialists; Infrastructural Enablers—Challenges linked to infrastructure, including high costs of investment and software/hardware upgrades; and Automation Enablers—Factors related to the adoption of automated processes, such as an unsupportive organizational culture, lack of experience and knowledge, and inadequate support from senior management. Conclusion: This research provides a comprehensive understanding of the enablers of digital poverty in BIM implementation among quantity surveyors in Lagos State. It highlights the multifaceted characteristics of these challenges and underscores the importance of addressing them to promote digital inclusion and leverage the advantages of digital technologies within the construction sector. The identified enablers can serve as a foundation for policymakers, organizations, and communities to develop targeted interventions aimed at reducing digital poverty and fostering a digitally inclusive environment for quantity surveyors in Lagos State.

References

[1]Abubakar M, Abdullahi M, Bala K. Analysis of the Causality Links between the Growth of the Construction Industry and the Growth of the Nigerian Economy. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries. 2018; 23(1): 103–113. doi: 10.21315/jcdc2018.23.1.6

[2]Khalfan M, Anumba C. Implementation of concurrent engineering in construction—readiness assessment. Available online: https://itc.scix.net/pdfs/w78-2000-544.content.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[3]Ammar A, Nassereddine H, AbdulBaky N, et al. Digital Twins in the Construction Industry: A Perspective of Practitioners and Building Authority. Frontiers in Built Environment. 2022; 8. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2022.834671

[4]Isa R, Jimoh R, Achuenu E. An overview of the contribution of the construction sector to sustainable development in Nigeria. Journal of business management. 2013; 1: 1–6.

[5]Thomas E. GlobalData: Nigeria’s construction industry to recover and grow by 3.9% in 2021. Available online: https://www.worldcement.com/africa-middle-east/19052021/globaldata-nigerias-construction-industry-to-recover-and-grow-by-39-in-2021/ (accessed on 25 August 2024).

[6]Kejriwal S, Mahajan S. Smart buildings: How IoT technology aims to add value for real estate companies: The Internet of Things in CRE industry. Delotte University Press; 2016;

[7]Kulasekara G, Jayasena H, Ariyachandra M. Comparative effectiveness of quantity surveying in BIM implementation. University of Moratuwa; 2016.

[8]Ojo G, Ebunoluwa E. Risk matrix analysis approach of marketing of construction professional services. Journal of the Nigerian Institute of Quantity Surveying. 2019; 65(1): 30–40.

[9]Oke A, Atofarati J, Bello S. Awareness of 3D Printing for Sustainable Construction in an Emerging Economy. Construction Economics and Building. 2022; 22(2). doi: 10.5130/ajceb.v22i2.8015

[10]Idoro G. Evaluating Levels of Project Planning and their Effects on Performance in the Nigerian Construction Industry. Construction Economics and Building. 2012; 9(2): 39–50. doi: 10.5130/ajceb.v9i2.3020

[11]Aje IO, Awodele OA. A study of the ethical values of quantity surveyors in Nigeria. In a 2-day national seminar on Ethical issues and the challenges in construction professionals’ service delivery 2006.

[12]Flyvbjerg B. Over Budget, Over Time, Over and Over Again. Oxford University Press; 2011.

[13]CIQS. What is quantity surveying?. Available online: https://ciqs.org/web/web/01-About-Us-Pages/What-is-quantity-surveying.aspx (accessed on 25 August 2024).

[14]Ashworth A, Hogg K, Higgs C. Willis’s Practice and Procedure for the Quantity Surveyor, 13th ed. Hoboken, Wiley; 2013.

[15]Mariam HIA, Khater M, Zaki M. Digital Business Transformation and Strategy: What Do We Know So Far? Available online: https://cambridgeservicealliance.eng.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/2017NovPaper_Mariam.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[16]Smith P. Project Cost Management with 5D BIM. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2016; 226: 193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.

[17]Shehab A, Abdelalim A. Utilization BIM For Integrating Cost Estimation and Cost Control in Construction Projects. International Journal of Management and Commerce Innovations. 2023; doi: 10.5281/zenodo.7923308.

[18]Mahamadu AM, Mahdjoubi L, Booth C. The integration of drones in quantity surveying practice: A systematic review. Journal of Construction Innovation. 2021; 21(4): 678–694.

[19]Chowdhury N. Information and Communications Technologies and IFPRI’s Mandate: A Conceptual Framework. Available online: https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital/collection/p15738coll2/id/125395 (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[20]Obasa AJ, Akinradewo OF, Olanipekun AO. Impact of technologies towards addressing stress-related problems among practicing quantity surveyors in Lagos, Nigeria. International Journal of Construction Management. 2022; 24(6): 623–632. doi: 10.1080/15623599.2022.2135943

[21]Ayodeji O, Victor A, Olumide T. An empirical study on challenges to the adoption of the Internet of Things in the Nigerian construction industry. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development. 2020.

[22]Autodesk BIM. Awards 2015—Hong Kong, Macau & Taiwan. Available online: https://download.autodesk.com/temp/pdf/Autodesk-BIM-Awards-2015-Booklet.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[23]Olanrewaju O, Ajiboye Babarinde S, Salihu C. Current State of Building Information Modelling in the Nigerian Construction Industry. Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Civil Engineering. 2020; 27(2): 63–77. doi: 10.5755/j01.sace.27.2.25142

[24]Pishdad P, Onungwa IO. Analysis of 5D BIM for cost estimation, cost control and payments. Journal of Information Technology in Construction. 2024; 29: 525–548. doi: 10.36680/j.itcon.2024.024

[25]Nvod I, Kawmudi N. Investigating the Challenges of Software Adoption Among Quantity Surveyors in Sri Lanka. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nethmi-Kawmudi-2/publication/387322497_Investigating_The_Challenges_of_Software_Adoption_Among_Quantity_Surveyors_in_Sri_Lanka/links/6768f10ae74ca64e1f254fa0/Investigating-The-Challenges-of-Software-Adoption-Among-Quantity-Surveyors-in-Sri-Lanka.pdf. 2024 (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[26]Ali KN, Alhajlah HH, Kassem MA. Collaboration and Risk in Building Information Modelling (BIM): A Systematic Literature Review. Buildings. 2022; 12(5): 571. doi: 10.3390/buildings12050571

[27]Gan VJL, Luo H, Tan Y, et al. BIM and Data-Driven Predictive Analysis of Optimum Thermal Comfort for Indoor Environment. Sensors. 2021; 21(13): 4401. doi: 10.3390/s21134401

[28]Růžička J, Veselka J, Rudovský Z, et al. BIM and Automation in Complex Building Assessment. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4): 2237. doi: 10.3390/su14042237

[29]Saada M, Aslan H. The effectiveness of applying BIM in increasing the accuracy of estimating quantities for public facilities rehabilitation projects in Syria after the war. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science. 2022; 5(2): 08–18. doi: 10.54216/ijbes.050201

[30]De Simone Z, Zheng T, Xu TB, et al. FlexiArch: A computational tool to assess the longevity of buildings through flexibility. Journal of Building Engineering. 2023; 78: 107178. doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107178

[31]Gharaibeh L, Lantz B, Eriksson KM. Bridging the gap: a framework for monetizing BIM by integrating industry insights for informed decision-making. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment; 2024.

[32]Thomas K. Building Information Modeling in quantity surveying education. Kuala Lumpur, Northumbria Research Link. 2012; 25–26.

[33]Ebekozien A, Aigbavboa C, Samsurijan MS, et al. BIM implementation for Nigeria’s polytechnic built environment undergraduates: challenges and possible measures from stakeholders. Facilities. 2024; 42(15/16): 70–91. doi: 10.1108/f-07-2023-0058

[34]World Bank. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2023: Turning the Tide. 2023; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/poverty-and-shared-prosperity (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[35]May J, Waema TM, Bjåstad E. Introduction: The ICT/poverty nexus in Africa. ICT Pathways to Poverty Reduction. 2014: 1–31. doi: 10.3362/9781780448152.001

[36]Ibrahim H, Liu X, Zariffa N, et al. Health data poverty: An assailable barrier to equitable digital health care. The Lancet Digital Health. 2021; 3(4): e260–e265. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30317-4

[37]Akinkuotu E. Number of poor Nigerians rises to 91 million—World poverty. 2020; Available online: https://punchng.com/number-of-poor-nigerians-rises-to-91-million-world-poverty-clock/ (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[38]Adejuwon K, Tijani A. Poverty reduction and the attainment of the millennium development goals in Nigeria: Problems and prospects. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences. 2012; 2(2): 53–74.

[39]Aidelunuoghene S. The paradox of poverty in Nigeria: What an irony. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting. 2014; 5(4): 116–122.

[40]Barrantes R. Digital poverty: An analytical framework. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Digital-poverty-%3A-An-analytical-framework-Barrantes/87c6dbfe73384e64f4f8a19d9cd4df2f764321fa (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[41]Beaunoyer E, Dupéré S, Guitton MJ. COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020; 111: 106424. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

[42]Donaghy D. Defining Digital Capital and Digital Poverty. ITNOW. 2021; 63(1): 54–55. doi: 10.1093/itnow/bwab025

[43]Lee H, Lee SH, Choi JA. Redefining Digital Poverty: A Study on Target Changes of the Digital Divide Survey for Disabilities: Low-Income and Elders. Journal of digital convergence. 2016; 14(3): 1–12. doi: 10.14400/JDC.2016.14.3.1

[44]Manduna W. Empirical Study of Digital Poverty: A Case Study of a University of Technology in South Africa. Journal of Communication. 2016; 7(2): 317–323. doi: 10.1080/0976691x.2016.11884913

[45]Angela SB, Mario I, Younes N. Rethinking poverty: An econometric analysis of the role of ICT poverty in a global context, Telecommunications Policy. 2024; 49 (1). doi: 0.1016/j.telpol.2024.102876.

[46]Arayici Y, Aouad G. Building information modeling (BIM) for construction lifecycle management. In: Construction and Building: Design, Materials, and Techniques. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2010. pp. 99–118.

[47]Eadie R, Browne M, Odeyinka H, et al. BIM implementation throughout the UK construction project lifecycle: An analysis. Automation in Construction. 2013; 36: 145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.autcon.2013.09.001

[48]NBS. National BIM Report 2012. Available online: https://buildinginformationmanagement.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/nbs-nationalbimreport12.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[49]Bernstein HM, Jones SA, Russo MA. The business value of BIM in North. McGraw-Hill Construction; 2012.

[50]Bednarczyk D. Counteracting digital exclusion (e-integration) in Poland. EBIB Newsletter. 2014; 9(154): 1–12.

[51]Won J, Lee G, Dossick C, Messner J. Where to focus for successful adoption of building information modeling within the organization. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. 2013; 139. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000731

[52]Jain NE. Marketing and the consumer decision making process. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/E-Marketing-and-the-consumer-decision-making-Jain/f7723acb4023934ca81104920611c5c68fb35a9e (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[53]Daniel K, Rogers T, Rostislav Z, et al. Digital Connectivity during Covid-19: Access to vital information for every child. UNICEF. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_url?url=https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/6186/file/UNICEF-IRB-Digital-Connectivity-During-Covid-19-2020-cover.pdf&hl=en&sa=X&ei=fmiDZqyOA-PTy9YPncyQqAs&scisig=AFWwaebRWrF-7q13ToS-ND8huDwn&oi=scholar (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[54]Moser CA, Kalton G. Survey Methods in Social Iinvestigation. Routledge; 2017.

[55]Kent MG. The importance of window view: Using an exploratory factor analysis to uncover the underlying latent dimensions. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mj1b1vz. 2018 (accessed on 28 September 2024).

[56]Hamed T, Shamsul S, Neda J. Exploratory Factor Analysis; Concepts and Theory. Jerzy Balicki. Advances in Applied and Pure Mathematics, 27, WSEAS. 2014. pp. 375-382.

[57]Mvududu NH, Sink CA. Factor analysis in counseling research and practice. Counseling Outcome Research & Evaluation. 2013; 4, 75–98.

[58]Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education. 2011; 2: 53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

[59]Pallant J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS. Allen and Unwin, Australia; 2011.

[60]Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLSSEM). SAGE Publications Ltd; 2017.

Copyright (c) 2025 Author(s)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.