Testing social impact and self-attention predictions with live audiences and co-actors

Abstract

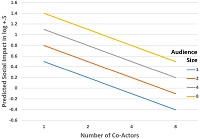

This experiment examined the influences of the number of co-actors and audience size on manual dexterity task performance and subjective reactions such as perceived effort and arousal. Predictions derived from social impact theory and the self-attention perspective’s other-total ratio indicated that both the number of co-actors and audience size should influence responses. Undergraduate students (N = 128) responded as 1, 2, 4, or 8 group members who were observed in a counterbalanced fashion by 1, 2, 4, or 8 audience members for four performance trials. The predictions of increased task performance with larger audience sizes and decreased performance as the number of co-actors increased were not supported. Participants rated arousal as somewhat consistent with the predictions from the self-attention perspective and social impact theory. Self-reported effort was consistent with the predicted patterns, but not always significantly so. The influence of the number of others is moderated by the objective-subjective nature of the responses of real co-actors performing in front of live audiences.

References

Allport, G. (1954). The historical background of modern social psychology. In: Lindzey, G. (editor). Handbook of social psychology. Addison-Wesley.

Baron, R. S. (1986). Distraction-conflict theory: Progress and problems. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 1-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60211-7

Baumeister, R. F., & Showers, C. J. (1986). A review of paradoxical performance effects: Choking under pressure in sports and mental tests. European Journal of Social Psychology, 16(4), 361-383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420160405

Birnbaum, M. H. (1973). The devil rides again: Correlation as an index of fit. Psychological Bulletin, 79(4), 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0033853

Bond, C. F., & Titus, L. J. (1983). Social facilitation: A meta-analysis of 241 studies. Psychological Bulletin, 94(2), 265–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.94.2.265

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1981). Attention and Self-Regulation. Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-5887-2

Chung, S., Lount, R. B., Park, H. M., et al. (2018). Friends With Performance Benefits: A Meta-Analysis on the Relationship Between Friendship and Group Performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217733069

Davis, J. H. (1969). Group performance. Addison-Wesley.

Forsyth, D. R. (2019). Group dynamics. Cengage Learning.

Geen, R. G. (1980). The effects of being observed on performance. In: Paulus, P. B. (editor). Psychology of group influence. Erlbaum.

Harkins, S. G., & Latané, B. (1998). Population and political participation: A social impact analysis of voter responsibility. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2(3), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.2.3.192

Jackson, J. M., & Latané, B. (1981). All alone in front of all those people: Stage fright as a function of number and type of co-performers and audience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.40.1.73

Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 681–706. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.681

Klonek, F. E., Gerpott, F. H., & Handke, L. (2023). When Groups of Different Sizes Collide: Effects of Targeted Verbal Aggression on Intragroup Functioning. Group & Organization Management, 48(4), 1203–1244. https://doi.org/10.1177/10596011221134426

Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36(4), 343–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.36.4.343

Latané, B., & Harkins, S. (1976). Cross-modality matches suggest anticipated stage fright a multiplicative power function of audience size and status. Perception & Psychophysics, 20(6), 482–488. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03208286

Latané, B., Liu, J. H., Nowak, A., et al. (1995). Distance Matters: Physical Space and Social Impact. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(8), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295218002

Latané, B., & Nida, S. (1981). Ten years of research on group size and helping. Psychological Bulletin, 89(2), 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.89.2.308

Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(6), 822–832. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.6.822

Martens, R., & Landers, D. M. (1972). Evaluation potential as a determinant of co-action effects. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 8(4), 347-359. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(72)90024-8

Mir, I., & Zaheer, A. (2012). Verification of social impact theory claims in social media context. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, 17(1).

Mullen, B. (1983). Operationalizing the effect of the group on the individual: A self-attention perspective. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19(4), 295-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(83)90025-2

Mullen, B. (1985). Strength and immediacy of sources: A meta-analytic evaluation of the forgotten elements of social impact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(6), 1458-1466. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.6.1458

Mullen, B. (1987). Self-attention theory: The effects of group composition on the individual. In: Mullen, B. & Goethals, G. R. (editors). Theories of Group Behavior. Springer.

Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957). The measurement of meaning. University of Illinois Press.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1980). Private and public self-attention, resistance to change and dissonance reduction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 390-405. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.390

Sedikides, C., & Jackson, J. M. (1990). Social impact theory: A field test of source strength, source immediacy and number of targets. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 11(3), 273-281. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1103_4

Tindale, R. S., Davis, J. H., Vollrath, D. A., et al. (1990). Asymmetrical social influence in freely interacting groups: A test of three models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(3), 438-449. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.3.438

Torka, A.-K., Mazei, J., & Hüffmeier, J. (2021). Together, everyone achieves more—or, less? An interdisciplinary meta-analysis on effort gains and losses in teams. Psychological Bulletin, 147(5), 504-534. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000251

Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. The American Journal of Psychology, 9(4), 507-533. https://doi.org/10.2307/1412188

Wicklund, R. A. (1980). Group contact and self-focused attention. In: Paulus, P. B. (editor). Psychology of group influence. Erlbaum.

Williams, K. B., & Williams, K. D. (1983). Social inhibition and asking for help: The effects of number, strength, and immediacy of potential help givers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 67-77. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.67

Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149(3681), 269-274. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.149.3681.269

Zell, E., Strickhouser, J. E., Sedikides, C., & Alicke, M. D. (2020). The better-than-average effect in comparative self-evaluation: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(2), 118-149. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000218

Copyright (c) 2024 Verlin B. Hinsz

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.