Gene recognition and role of foodomics in mycotoxin control: A review

Abstract

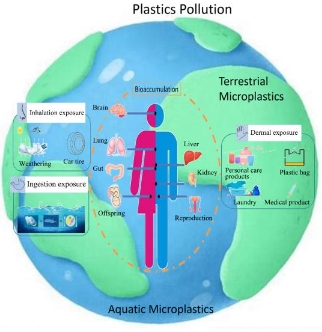

Since recognition of toxic and carcinogenic aflatoxins in Brazilian groundnut meal in 1960, much research has been done to prevent and detoxify aflatoxins in foods and feeds, identifying a variety of methods. The research has expanded to other mycotoxins. The biotic and abiotic factors favoring mycotoxin contaminations have been understood through experiments under laboratory conditions and analysis of field data. However, many gaps remain in the knowledge on mycotoxin control at the molecular level that may be useful in addressing mycotoxigenic hazards. Recognition of responsible genes in hosts and fungi and omics methods applying genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to understand mycotoxin biosynthesis at the molecular level may open new avenues to interact with plant-fungi-bacteria cross-talks, apply regulatory mechanisms in biosynthesis, and explore checks and controls addressing abiotic and biotic factors favoring mycotoxin biosynthesis. The new knowledge is expected to generate probable molecular biological mechanisms to eliminate mycotoxin biosynthesis on foods. The current level of omics knowledge requires application of research to achieve deeper understanding, aiming at new methods for mycotoxin controls and applying next-generation technologies. This review examines the current knowledge on the biosynthesis of aflatoxins, fusarium toxins, and patulin in foods and host-fungi interactions at a molecular level.

References

[1]Allcroft R, Carnaghan RBA, Sargeant K. et al. A toxic factor in Brazilian groundnut meal. Veterinary Record; 1961; 73: 428-429.

[2]Samarajeewa U. Agronomic Prevention of Pre-Harvest Mycotoxin Contamination in Foods: A Review. Food Science and Nutrition. 2024; 10(4): 1-8. doi: 10.24966/fsn-1076/100192

[3]Samarajeewa U, Sen AC, Cohen MD, et al. Detoxification of Aflatoxins in Foods and Feeds by Physical and Chemical Methods. Journal of Food Protection. 1990; 53(6): 489-501. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-53.6.489

[4]Chang PK, Yabe K, Yu J. The Aspergillus parasiticus estA -Encoded Esterase Converts Versiconal Hemiacetal Acetate to Versiconal and Versiconol Acetate to Versiconol in Aflatoxin Biosynthesis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004; 70(6): 3593-3599. doi: 10.1128/aem.70.6.3593-3599.2004

[5]Cary JW, Rajasekaran K, Brown RL, et al. Developing Resistance to Aflatoxin in Maize and Cottonseed. Toxins. 2011; 3(6): 678-696. doi: 10.3390/toxins3060678

[6]Bhatnagar D, Rajasekaran K, Gilbert M, et al. Advances in molecular and genomic research to safeguard food and feed supply from aflatoxin contamination. World Mycotoxin Journal. 2018; 11(1): 47-72. doi: 10.3920/wmj2017.2283

[7]Bhatnagar D, Rajasekaran K, Payne G, et al. The “omics” tools: genomics, proteomics, metabolomics and their potential for solving the aflatoxin contamination problem. World Mycotoxin Journal. 2008; 1(1): 3-12. doi: 10.3920/wmj2008.x001

[8]Chen ZY, Rajasekaran K, Brown RL, et al. Discovery and confirmation of genes/proteins associated with maize aflatoxin resistance. World Mycotoxin Journal. 2015; 8(2): 211-224. doi: 10.3920/wmj2014.1732

[9]Soni P, Gangurde SS, Ortega-Beltran A, et al. Functional Biology and Molecular Mechanisms of Host-Pathogen Interactions for Aflatoxin Contamination in Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and Maize (Zea mays L.). Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020; 11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00227

[10]Yu B, Huai D, Huang L, et al. Identification of genomic regions and diagnostic markers for resistance to aflatoxin contamination in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). BMC Genetics. 2019; 20(1). doi: 10.1186/s12863-019-0734-z

[11]Liao B, Zhuang W, Tang R, et al. Peanut Aflatoxin and Genomics Research in China: Progress and Perspectives. Peanut Science. 2009; 36(1): 21-28. doi: 10.3146/at07-004.1

[12]Cao A, de la Fuente M, Gesteiro N, et al. Genomics and Pathways Involved in Maize Resistance to Fusarium Ear Rot and Kernel Contamination With Fumonisins. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2022; 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.866478

[13]Xu Q, Xu F, Qin D, et al. Molecular Mapping of QTLs Conferring Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Chinese Wheat Cultivar Jingzhou 66. Plants. 2020; 9(8): 1021. doi: 10.3390/plants9081021

[14]Ciasca B, Lanubile A, Marocco A, et al. Application of an Integrated and Open Source Workflow for LC-HRMS Plant Metabolomics Studies. Case-Control Study: Metabolic Changes of Maize in Response to Fusarium verticillioides Infection. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2020; 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00664

[15]Santiago R, Cao A, Malvar RA, et al. Genomics of Maize Resistance to Fusarium Ear Rot and Fumonisin Contamination. Toxins. 2020; 12(7): 431. doi: 10.3390/toxins12070431

[16]Cleveland TE, Dowd PF, Desjardins AE, et al. United States Department of Agriculture—Agricultural Research Service research on pre‐harvest prevention of mycotoxins and mycotoxigenic fungi in US crops. Pest Management Science. 2003; 59(6-7): 629-642. doi: 10.1002/ps.724

[17]Yu J. Current Understanding on Aflatoxin Biosynthesis and Future Perspective in Reducing Aflatoxin Contamination. Toxins. 2012; 4(11): 1024-1057. doi: 10.3390/toxins4111024

[18]Pandey MK, Kumar R, Pandey AK, et al. Mitigating Aflatoxin Contamination in Groundnut through A Combination of Genetic Resistance and Post-Harvest Management Practices. Toxins. 2019; 11(6): 315. doi: 10.3390/toxins11060315

[19]Wang T, Zhang E, Chen X, et al. Identification of seed proteins associated with resistance to pre-harvested aflatoxin contamination in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). BMC Plant Biology. 2010; 10(1). doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-267

[20]Fountain JC, Khera P, Yang L, et al. Resistance to Aspergillus flavus in maize and peanut: Molecular biology, breeding, environmental stress, and future perspectives. The Crop Journal. 2015; 3(3): 229-237. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2015.02.003

[21]Cui M, Han S, Wang D, et al. Gene Co-expression Network Analysis of the Comparative Transcriptome Identifies Hub Genes Associated With Resistance to Aspergillus flavus L. in Cultivated Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Frontiers in Plant Science. 2022; 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.899177

[22]Eshelli M, Qader MM, Jambi EJ, et al. Current Status and Future Opportunities of Omics Tools in Mycotoxin Research. Toxins. 2018; 10(11): 433. doi: 10.3390/toxins10110433

[23]Bhatnagar D, Ehrlich KC, Cleveland TE. Molecular genetic analysis and regulation of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2003; 61(2): 83-93. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1199-x

[24]Yu J, Chang PK, Ehrlich KC, et al. Clustered Pathway Genes in Aflatoxin Biosynthesis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004; 70(3): 1253-1262. doi: 10.1128/aem.70.3.1253-1262.2004

[25]Liu BH, Chu FS. Regulation ofaflRand Its Product, AflR, Associated with Aflatoxin Biosynthesis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1998; 64(10): 3718-3723. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3718-3723.1998

[26]Natarajan S, Balachandar D, Senthil N, et al. Interaction of water activity and temperature on growth, gene expression, and aflatoxin B1 production in Aspergillus flavus on Indian senna (Cassia angustifolia Vahl.). International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2022; 361: 109457. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109457

[27]Schmidt-Heydt M, Abdel-Hadi A, Magan N, et al. Complex regulation of the aflatoxin biosynthesis gene cluster of Aspergillus flavus in relation to various combinations of water activity and temperature. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2009; 135(3): 231-237. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.026

[28]Schmidt-Heydt M, Rüfer CE, Abdel-Hadi A, et al. The production of aflatoxin B1 or G1 by Aspergillus parasiticus at various combinations of temperature and water activity is related to the ratio of aflS to aflR expression. Mycotoxin Research. 2010; 26(4): 241-246. doi: 10.1007/s12550-010-0062-7

[29]Abdel-Hadi A, Schmidt-Heydt M, Parra R, et al. A systems approach to model the relationship between aflatoxin gene cluster expression, environmental factors, growth and toxin production by Aspergillus flavus. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 2011; 9(69): 757-767. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0482

[30]Yusuf HO, Olu J, Ajenifujah-Solebo SO, et al. Identification and Sequencing of aflP (omt) and aflD (Nor-1) Genes from Aspergillus flavus Species isolated from Maize (Zea mays L.), Obtained Across Abuja, Nigeria. Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2022; 1(1): 10-19. doi: 10.36108/jbmb/2202.10.0120

[31]Katati B, Kovacs S, Njapau H, et al. Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Modulates Aflatoxin-B1 Levels through an Antioxidative Mechanism. Journal of Fungi. 2023; 9(6): 690. doi: 10.3390/jof9060690

[32]Al-Saad LA, Al-Badran AI, Al-Jumayli SA, et al. Impact of bacterial biocontrol agents on aflatoxin biosynthetic genes, aflD and aflR expression, and phenotypic aflatoxin B1 production by Aspergillus flavus under different environmental and nutritional regimes. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2016; 217: 123-129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.10.016

[33]Mannaa M, Kim KD. Influence of Temperature and Water Activity on Deleterious Fungi and Mycotoxin Production during Grain Storage. Mycobiology. 2017; 45(4): 240-254. doi: 10.5941/myco.2017.45.4.240

[34]Medina Á, Rodríguez A, Sultan Y, et al. Climate change factors andAspergillus flavus: effects on gene expression, growth and aflatoxin production. World Mycotoxin Journal. 2015; 8(2): 171-180. doi: 10.3920/wmj2014.1726

[35]Wang X, Zha W, Yao B, et al. Genetic Interaction of Global Regulators AflatfA and AflatfB Mediating Development, Stress Response and Aflatoxins B1 Production in Aspergillus flavus. Toxins. 2022; 14(12): 857. doi: 10.3390/toxins14120857

[36]McDonald T, Brown D, Keller NP, et al. RNA silencing of mycotoxin production in Aspergillus and Fusarium species. Molecular Plant Microbe Interactions. 2005; 18(6): 539-545. DOI: 10.1094/ MPMI -18-0539.

[37]Thakare D, Zhang J, Wing RA, et al. Aflatoxin-free transgenic maize using host-induced gene silencing. Science Advances. 2017; 3(3). doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602382

[38]Sharma KK, Pothana A, Prasad K, et al. Peanuts that keep aflatoxin at bay: a threshold that matters. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2017; 16(5): 1024-1033. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12846

[39]Loi M, Logrieco AF, Pusztahelyi T, et al. Advanced mycotoxin control and decontamination techniques in view of an increased aflatoxin risk in Europe due to climate change. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2023; 13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1085891

[40]Bernáldez V, Córdoba JJ, Magan N, et al. The influence of ecophysiological factors on growth, aflR gene expression and aflatoxin B1 production by a type strain of Aspergillus flavus. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2017; 83: 283-291. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.05.030

[41]Caceres I, Al Khoury A, El Khoury R, et al. Aflatoxin Biosynthesis and Genetic Regulation: A Review. Toxins. 2020; 12(3): 150. doi: 10.3390/toxins12030150

[42]Musungu BM, Bhatnagar D, Brown RL, et al. A Network Approach of Gene Co-expression in the Zea mays/Aspergillus flavus Pathosystem to Map Host/Pathogen Interaction Pathways. Frontiers in Genetics. 2016; 7. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00206

[43]Huff WE, Hamilton PB. Mycotoxins – Their Biosynthesis in Fungi: Ochratoxins – Metabolites of Combined Pathways. Journal of Food Protection. 1979; 42(10): 815-820. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-42.10.815

[44]Harris JP, Mantle PG. Biosynthesis of ochratoxins by Aspergillus ochraceus. Phytochemistry. 2001; 58:709-716. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00316-8

[45]Gallo A, Bruno KS, Solfrizzo M, et al. New Insight into the Ochratoxin A Biosynthetic Pathway through Deletion of a Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase Gene in Aspergillus carbonarius. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012; 78(23): 8208-8218. doi: 10.1128/aem.02508-12

[46]Wang Y, Wang L, Wu F, et al. A Consensus Ochratoxin A Biosynthetic Pathway: Insights from the Genome Sequence of Aspergillus ochraceus and a Comparative Genomic Analysis. Drake HL, ed. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2018; 84(19). doi: 10.1128/aem.01009-18

[47]Vanacloig-Pedros E, Proft M, Pascual-Ahuir A. Different Toxicity Mechanisms for Citrinin and Ochratoxin A Revealed by Transcriptomic Analysis in Yeast. Toxins. 2016; 8(10): 273. doi: 10.3390/toxins8100273

[48]Merhej J, Richard-Forget F, Barreau C. Regulation of trichothecene biosynthesis in Fusarium: recent advances and new insights. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2011; 91(3): 519-528. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3397-x

[49]Wang J, Zhang M, Yang J, et al. Type A Trichothecene Metabolic Profile Differentiation, Mechanisms, Biosynthetic Pathways, and Evolution in Fusarium Species—A Mini Review. Toxins. 2023; 15(7): 446. doi: 10.3390/toxins15070446

[50]Kimura M, Tokai T, Takahashi-Ando N, et al. Molecular and Genetic Studies of FusariumTrichothecene Biosynthesis: Pathways, Genes, and Evolution. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 2007; 71(9): 2105-2123. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70183

[51]Proctor RH, McCormick SP, Alexander NJ, et al. Evidence that a secondary metabolic biosynthetic gene cluster has grown by gene relocation during evolution of the filamentous fungus Fusarium. Molecular Microbiology. 2009; 74(5): 1128-1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06927.x

[52]Yli-Mattila T, Hussien T, Abbas A. Comparison of biomass and deoxynivalenol production of northern European and southern European Fusarium graminearum isolates in the infection of wheat and oat grains. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2022; 104(4): 1465-1474. doi: 10.1007/s42161-022-01233-9

[53]Alexander NJ, McCormick SP, Waalwijk C, et al. The genetic basis for 3-ADON and 15-ADON trichothecene chemotypes in Fusarium. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2011; 48(5): 485-495. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2011.01.003

[54]Seong K, Pasquali M, Zhou X, et al. Global gene regulation by Fusarium transcription factors Tri6 and Tri10 reveals adaptations for toxin biosynthesis. Molecular Microbiology. 2009; 72(2): 354-367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06649.x

[55]Kim JE, Son H, Lee YW. Biosynthetic mechanism and regulation of zearalenone in Fusarium graminearum. Japanese Society of Mycotoxicology and Mycotoxins. 2018; 68(1): 1-6. doi: 10.2520/myco.68-1-2

[56]Mahato DK, Devi S, Pandhi S, et al. Occurrence, impact on agriculture, human health, and management strategies of zearalenone in food and feed: A review. Toxins. 2021; 13: 92. doi: 10.3390/ toxins13020092

[57]Lysøe E, Klemsdal SS, Bone KR, et al. The PKS4 Gene of Fusarium graminearum Is Essential for Zearalenone Production. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006; 72(6): 3924-3932. doi: 10.1128/aem.00963-05

[58]Li B, Zong Y, Du Z, et al. Genomic Characterization Reveals Insights Into Patulin Biosynthesis and Pathogenicity in Penicillium Species. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions®. 2015; 28(6): 635-647. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-12-14-0398-fi

[59]Snini SP, Tadrist S, Laffitte J, et al. The gene PatG involved in the biosynthesis pathway of patulin, a food-borne mycotoxin, encodes a 6-methylsalicylic acid decarboxylase. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2014; 171: 77-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.11.020

[60]Guche MD, Pilati S, Trenti F, et al. Functional Study of Lipoxygenase-Mediated Resistance against Fusarium verticillioides and Aspergillus flavus Infection in Maize. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(18): 10894. doi: 10.3390/ijms231810894

[61]Rashad YM, Abdalla SA, Shehata AS. Aspergillus flavus YRB2 from Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl., a non-aflatoxigenic endophyte with ability to overexpress defense-related genes against Fusarium root rot of maize. BMC Microbiology. 2022; 22(1). doi: 10.1186/s12866-022-02651-6

[62]Qiu M, Deng Y, Deng Q, et al. Cysteine Inhibits the Growth of Fusarium oxysporum and Promotes T-2 Toxin Synthesis through the Gtr/Tap42 Pathway. Microbiology Spectrum. 2022; 10(6). doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03682-22

[63]Murtaza B, Li X, Nawaz MY, et al. Toxicodynamic of combined mycotoxins: MicroRNAs and acute‐phase proteins as diagnostic biomarkers. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2024; 23(3). doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.13338

[64]Huang JH, and Hsieh DP. Comparative study of aflatoxins M1 and B1 production in solid-state and shaking liquid cultures. In: Proceedings of the National Science Council Republic China; 1988.

[65]Garrido NS, Iha MH, Santos Ortolani MR, et al. Occurrence of aflatoxins M1and M2in milk commercialized in Ribeirão Preto-SP, Brazil. Food Additives and Contaminants. 2003; 20(1): 70-73. doi: 10.1080/0265203021000035371

[66]Cortinovis C, Caloni F, Schreiber NB, et al. Effects of fumonisin B1 alone and combined with deoxynivalenol or zearalenone on porcine granulosa cell proliferation and steroid production. Theriogenology. 2014; 81(8): 1042-1049. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2014.01.027

[67]Berthiller F, Crews C, Dall’Asta C, et al. Masked mycotoxins: A review. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2012; 57(1): 165-186. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100764

[68]Zhang J, Chiodini R, Badr A, et al. The impact of next-generation sequencing on genomics. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 2011; 38(3): 95-109. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2011.02.003

[69]Venkatesh N, Keller NP. Mycotoxins in Conversation With Bacteria and Fungi. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2019; 10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00403

Copyright (c) 2024 Upali Samarajeewa

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.