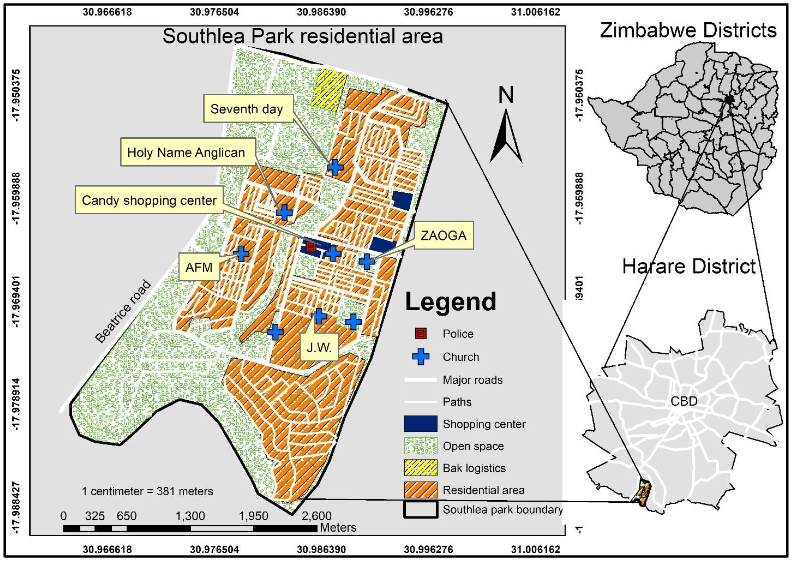

COVID-19 induced DV in Zimbabwe’s Southlea Park residential area in Harare

Abstract

COVID-19 affected various communities across the globe in different ways. The study assessed the impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on domestic violence in the Southlea-Park residential area in Harare. A mixed-methods research design was adopted as it allowed use of both qualitative and quantitative data collection approaches. Questionnaires, interviews, and observations were employed for data collection. The research showed that DV in the Southlea Park residential area emanated from drug abuse, juvenile delinquency, conflicts over decision-making between parents, prostitution, and food insufficiency, among others. The study indicated that most dominant forms of DV in Southlea Park during the COVID-19 lockdown period included physical, emotional, and verbal violence. The findings from this study indicated that males suffered more from verbal and psychological violence, while females suffered more from physical, economic, sexual, and emotional violence. The research concludes that COVID-19 had massive influence on domestic violence; however, the Zimbabwe Republic Police should ensure deployment of police officers in temporary camps within or close to residential areas that are far from police stations to ensure public safety during situations that trigger domestic and other forms of violence in residential areas, and the Ministry of Women Affairs, Community, Small and Medium Enterprises Development in Zimbabwe should ensure availability of agents responsible for ensuring against vulnerability of people to gender, domestic, and other forms of violence in all communities of the country, especially during situations that trigger violence.

References

[1]Worku A, Addisie M. Sexual violence among female high school students in Debark, northwest Ethiopia. East African Medical Journal. 2002; 79(2). doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i2.8911

[2]Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. The lancet. 2002; 360(9339): 1083-1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0

[3]Coker AL, Richter DL. Violence against women in Sierra Leone: frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence and forced sexual intercourse. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 1998; 2(1): 61-72.

[4]Campello M, Kankanhalli G, Muthukrishnan P. Corporate Hiring under COVID-19: Labor Market Concentration, Downskilling, and Income Inequality. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27208/w27208.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

[5]Leslie E, Wilson R. Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics. 2020; 189: 104241. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104241

[6]Cajner T, Crane LD, Decker RA, et al. The US Labor Market during the Beginning of the Pandemic Recession. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 2020; 2020(2): 3-33. doi: 10.1353/eca.2020.0005

[7]Cowan BW. Short-run Effects of COVID-19 on US Worker Transitions. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27315/w27315.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

[8]Kahn LB, Lange F, Wiczer DG. Labor Demand in the time of COVID-19: Evidence from vacancy postings and UI claims. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27061/w27061.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

[9]Eslava M, Becerra O, Cárdenas JC, et al. The Socioeconomics of COVID and Lockdowns Outside Advanced Economies: The Case of Bogota Economía. 2023; 22(1). doi: 10.31389/eco.7

[10]Kourti A, Stavridou A, Panagouli E, et al. Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2021; 24(2): 719-745. doi: 10.1177/15248380211038690

[11]Catalá-Miñana A, Lila M, Oliver A, et al. Contextual Factors Related to Alcohol Abuse Among Intimate Partner Violence Offenders. Substance Use & Misuse. 2016; 52(3): 294-302. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1225097

[12]de Souza Santos D, Bittencourt EA, de Moraes Malinverni AC, et al. Domestic violence against women during the Covid-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Forensic Science International: Reports. 2022; 5: 100276. doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2022.100276

[13]Maji S, Bansod S, Singh T. Domestic violence during COVID‐19 pandemic: The case for Indian women. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 2021; 32(3): 374-381. doi: 10.1002/casp.2501

[14]Parkinson D. Investigating the Increase in Domestic Violence Post Disaster: An Australian Case Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017; 34(11): 2333-2362. doi: 10.1177/0886260517696876

[15]Zahran S, Shelley TO, Peek L, et al. Natural Disasters and Social Order: Modeling Crime Outcomes in Florida. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters. 2009; 27(1): 26-52. doi: 10.1177/028072700902700102

[16]Adams PR, Adams GR. Mount Saint Helens’s ashfall: Evidence for a disaster stress reaction. American Psychologist. 1984; 39(3): 252-260. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.39.3.252

[17]Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, Norris FH, et al. Intimate Partner Violence and Hurricane Katrina: Predictors and Associated Mental Health Outcomes. Violence and Victims. 2010; 25(5): 588-603. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.588

[18]Mak S. China’s hidden epidemic: Domestic violence. The Diplomat. 2020.

[19]Rauhaus BM, Sibila D, Johnson AF. Addressing the Increase of Domestic Violence and Abuse During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Need for Empathy, Care, and Social Equity in Collaborative Planning and Responses. The American Review of Public Administration. 2020; 50(6-7): 668-674. doi: 10.1177/0275074020942079

[20]Taub A. A new COVID-19 crisis: Domestic abuse rises worldwide. The New York Times. 2020; 6.

[21]Piquero AR, Riddell JR, Bishopp SA, et al. Staying Home, Staying Safe? A Short-Term Analysis of COVID-19 on Dallas Domestic Violence. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020; 45(4): 601-635. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09531-7

[22]Demir M, Park S. The Effect of COVID-19 on Domestic Violence and Assaults. Criminal Justice Review. 2021; 47(4): 445-463. doi: 10.1177/07340168211061160

[23]Homayounieh F, Ebrahimian S, Babaei R, et al. CT Radiomics, Radiologists, and Clinical Information in Predicting Outcome of Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020; 2(4): e200322. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200322

[24]Chuku C, Mukasa A, Yasin Y. Putting women and girls’ safety first in Africa’s response to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/putting-women-and-girls-safety-first-in-africas-response-to-covid-19/#:~:text=First%2C%20women%20in%20Africa%20are,as%2091%20percent%20in%20Egypt. (accessed on 10 November 2023).

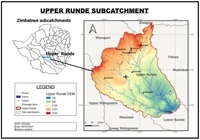

[25]Taru P. DV during coronavirus lockdown in the Zimfact. 2020.

[26]Silverio-Murillo A, de la Miyar JB, Hoehn-Velasco L. Families Under Confinement: COVID-19 and Domestic Violence. Crime and Social Control in Pandemic Times. 2023; 23-41. doi: 10.1108/s1521-613620230000028003

[27]Kabil M, Ali MA, Marzouk A, et al. Gender Perspectives in Tourism Studies: A Comparative Bibliometric Analysis in the MENA Region. Tourism Planning & Development. 2022; 1-23. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2022.2050419

[28]Kamusoko C, Gamba J, Murakami H. Monitoring urban spatial growth in Harare Metropolitan province, Zimbabwe. Advances in Remote Sensing. 2013.

[29]Baldock JW, Styles MT, Kalbskopf S, Muchemwa E. The Geology of the Harare Greenstone Belt and Surrounding Granitic Terrain. Zimbabwe Geological Survey; 1991.

[30]Vinyu ML, Jelsma HA, Frei R. Timing between granitoid emplacement and associated gold mineralization: examples from the ca. 2.7 Ga Harare–Shamva greenstone belt, northern Zimbabwe. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 1996; 33(7): 981-992. doi: 10.1139/e96-074

[31]Nyamapfene KW. The soils of Zimbabwe. In: Monitoring urban spatial growth in Harare Metropolitan province, Zimbabwe. Nehanda Publishers; 2013.

[32]Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). Zimbabwe Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2012, Snapshots of Key Findings. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT); 2012.

[33]Gamanya R, De Maeyer P, De Dapper M. Object-oriented change detection for the city of Harare, Zimbabwe. Expert Systems with Applications. 2009; 36(1): 571-588. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2007.09.067

[34]Mbiba B. Urban agriculture, the poor and planners: a Harare case study. In: Proceedings of the 10th Inter-Schools Conference on Development; 29-30 March 1993; London, UK. pp. 129-135.

[35]Puszczak K, Fronczyk A, Urbański M. Analysis of sample size in consumer surveys. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/db_indicators/surveys/documents/workshops/2013/pl-gfk_k._pusczak_-_sample_size_in_customer_surveys_v2_2.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

[36]Riggs DS, O’leary KD. Aggression between heterosexual dating partners: An examination of a causal model of courtship aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996; 11(4): 519-540.

[37]Putra IGNE, Pradnyani PE, Parwangsa NWPL. Vulnerability to domestic physical violence among married women in Indonesia. Journal of Health Research. 2019; 33(2): 90-105. doi: 10.1108/jhr-06-2018-0018

[38]Yari A, Zahednezhad H, Gheshlagh RG, et al. Frequency and determinants of domestic violence against Iranian women during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1). doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11791-9

[39]Schokkenbroek JM, Anrijs S, Ponnet K, et al. Locked Down Together: Determinants of Verbal Partner Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Violence and Gender. 2021; 8(3): 148-153. doi: 10.1089/vio.2020.0064

[40]Mahlangu P, Gibbs A, Shai N, et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown and link to women and children’s experiences of violence in the home in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1). doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13422-3

[41]Chiba H, Lewis M, Benjamin ER, et al. “Safer at home”: The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on epidemiology, resource utilization, and outcomes at a large urban trauma center. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2020; 90(4): 708-713. doi: 10.1097/ta.0000000000003061

[42]Barbara G, Facchin F, Micci L, et al. COVID-19, lockdown, and intimate partner violence: some data from an Italian service and suggestions for future approaches. Journal of Women’s Health. 2020; 29(10): 1239-1242.

Copyright (c) 2023 Oshneck Mupepi, Mark Matsa

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors contributing to this journal agree to publish their articles under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, allowing third parties to share their work (copy, distribute, transmit) and to adapt it for any purpose, even commercially, under the condition that the authors are given credit. With this license, authors hold the copyright.